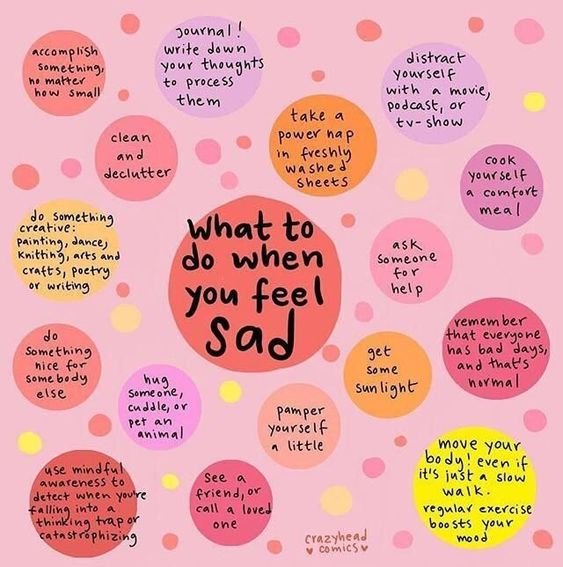

What To Do When You Feel Sad

Difficult Acts of Self Care

Be Like A River

Reach out and listen: How to help someone at risk of suicide

Reach out and listen: How to help someone at risk of suicide

December 15, 20207:45 AM ET

Updated Aug. 25, 2022

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by dialing 9-8-8, or the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741.

If you know someone struggling with despair, depression or thoughts of suicide, you may be wondering how to help.

Most Americans recently surveyed say that they understand that suicide is preventable and that they would act to help someone they know who is at risk.

Yet many of us are afraid to do the wrong thing. In fact, you don't have to be a trained professional to help, says Doreen Marshall, a psychologist and vice president of programs at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

"Everyone has a role to play in suicide prevention," she says. But "most people hold back. We often say, 'Trust your gut. If you're worried about someone, take that step.' "

And that first step starts with simply reaching out, says Marshall. It may seem like a small thing, but survivors of suicide attempts and suicide experts say, it can go long way.

If You Need Help: Resources

If you or someone you know is in crisis and need immediate help, call the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by dialing 9-8-8 or go here for online chat.

For more help:

Find 5 Action Steps for helping someone who may be suicidal, from the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

Six questions to ask to help assess the severity of someone's suicide risk, from the Columbia Lighthouse Project.

To prevent a future crisis, here's how to help someone make a safety plan.

Simple acts of connection are powerful, says Ursula Whiteside, a psychologist and a faculty member at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

"Looking out for each other in general reduces [suicide] risk," says Whiteside. "Because people who feel connected are less likely to kill themselves."

And "the earlier you catch someone," she adds, "the less they have to suffer."

Here are nine things you can do that can make a difference.

1. Recognize the warning signs

Signs of suicide risk to watch for include changes in mood and behavior, Marshall says.

"For example, someone who is usually part of a group or activity and you notice that they stop showing up," explains Marshall. "Someone who is usually pretty even-tempered and you see they are easily frustrated or angry."

If you're only seeing your loved ones virtually because of the pandemic, pay attention if they start withdrawing from virtual spaces, too, says Whiteside.

Maybe "they're not responding to phone calls or they're not joining in on a call with family or they're not on social media," she says. "That's one time that it makes sense to get curious about what's going on with your friend — when people start to disappear."

Other signs include feeling depressed, anxious, irritable or losing interest in things.

Pay attention to a person's words, too.

"They may talk about wanting to end their lives or seeing no purpose or wanting to go to sleep and never wake up," says Marshall. "Those are signs that they may be thinking about [suicide]. It may be couched as a need to get away from, or escape the pain."

According to the AFSP, people who take their own lives often show a combination of these warning signs.

And the signs can be different for different people, says Madelyn Gould, a professor of epidemiology in psychiatry at Columbia University who studies suicide and suicide prevention.

"For some people, it might be starting to have difficulty sleeping," she says. Someone else might easily feel humiliated or rejected.

"Each one of these things can put [someone] more at risk," explains Gould, "Until at some point, [they're] not in control anymore."

2. Reach out and ask, "Are you OK?"

So, what do you do when you notice someone is struggling and you fear they may be considering suicide?

Reach out, check in and show you care, say suicide prevention experts.

"The very nature of someone struggling with suicide and depression, [is that] they're not likely to reach out," says Marshall. "They feel like a burden to others."

People who are having thoughts of suicide often feel trapped and alone, explains DeQuincy Lezine, a psychologist and a member of the board of directors of the American Association of Suicidology. He is also a survivor of suicide attempts.

When someone reaches out and offers support, it reduces a person's sense of isolation, he explains.

"Even if you can't find the exact words [to say], the aspect that somebody cares makes a big difference," says Lezine.

Questions like "Are you doing OK?" and statements like "If you need anything, let me know" are simple supportive gestures that can have a big impact on someone who's in emotional pain, explains Julie DeGolier, a medical assistant in Seattle and a survivor of suicide attempts. It can interrupt the negative spiral that can lead to crisis.

The website for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline has a list of do's and don'ts when trying to help someone at risk.

3. Be direct: Ask about suicide

"Most people are afraid to ask about suicide, because they [think they] don't want to put the thought in their head," says Marshall. "But there's no research to support that."

Instead, she and other suicide prevention experts say discussing suicide directly and compassionately with a person at risk is key to preventing it.

One can ask a direct question like, "Have you ever had thoughts of suicide?" says Marshall.

More general questions like, "What do you think of people who kill themselves?" can also open up a conversation about suicide, says Gould. "Now they are talking about it, when you might not have had the conversation before."

4. Assess risk and don't panic: Suicidal feelings aren't always an emergency

Say a loved one confides in you that they have been thinking about suicide, what do you do then?

"Don't let yourself panic," says Whiteside.

People often believe that a person considering suicide needs to be rushed to the hospital. But "not everyone who expressed these thoughts needs to be hospitalized immediately," says Marshall.

Research shows that most people who've had suicidal thoughts haven't had the kind of overpowering thoughts that might push them to make an attempt, explains Whiteside. In other words, many more people experience suicidal thoughts than take action on them.

But how do you know whether your loved one's situation is an immediate crisis?

Whiteside suggests asking direct questions like: "Are you thinking of killing yourself in the next day or so?" and "How strong are those urges?"

For help with this conversation, psychiatrists at Columbia University have developed the Columbia Protocol, which is a risk-assessment tool drawn from their research-based suicide severity rating scale. It walks you through six questions to ask your loved one about whether they've had thoughts about suicide and about the means of suicide and whether they have worked out the details of how they would carry out their plan.

Someone who has a plan at hand is at a high risk of acting on it — according to the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, about 38 percent of people who have made a plan go on to make an attempt.

5. If it's a crisis, stick around

So what if you've assessed risk and you fear your loved one is in immediate crisis? First, request them to hold off for a day or so, says Whiteside, at the same time being "validating and gentle."

The kind of intense emotions that might make someone act on an impulse, "usually resolve or become manageable in less than 24 or 48 hours," she says. If you can, offer to stay with them during that time period, she adds. Or, if that's hard because of the pandemic, offer to be present virtually via video call. Otherwise, help them find other immediate social support or medical help. They shouldn't be alone at these times of crisis.

Ask whether they have any means of harming themselves at hand and work with them to remove those things from their environment. Research shows that removing or limiting access to means reduces suicide deaths.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline offers this guide to the five action steps to take if someone you know is imminent danger.

If you don't feel confident about helping someone through a crisis period, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, says Gould.

6. Listen and offer hope

If the person is not in immediate risk, it is still important to listen to them, say survivors of suicide attempts like Lezine and DeGolier.

"The biggest thing is listening in an open-minded way, to not be judgmental," says DeGolier.

"Don't tell a person what to do. They're looking to be heard, to have their feelings acknowledged."

The next step is to offer hope, says Whiteside. It helps to say things like, "I know how strong you are. I've seen you get through hard things. I think we can get through this together," she explains.

One of Lezine's closest friends in college did just that during his suicidal phases, he says.

"For one thing, she never lost faith in me," says Lezine. "She always believed I have a positive life possible and I would achieve good things."

He says her faith in him kept him from giving in to his despair completely.

"Having somebody, a confidante who absolutely believed as a person in [my] ability to do something meaningful in life" was instrumental in his recovery, he says.

7. Help your loved one make a safety plan

When a person is not in immediate risk of attempting suicide, it's a good time to think about preventing a future crisis.

"That's where we want to make help-seeking and adaptive coping strategies a practice," says Gould.

Suicide prevention experts advise people develop what's known as a safety plan, which research has shown can help reduce suicide risk. It's a simple plan for how to cope and get help when a crisis hits, and typically, an at-risk person and their mental health provider create it together, but a family member or friend can also help.

The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention has a template for creating a safety plan. It includes making a list of the person's triggers and warning signs of a coming crisis, people they feel comfortable reaching out to for help and activities they can do to distract themselves during those times — it can be something simple as watching a funny movie.

Safety planning includes helping your loved one make their environment safer. This includes a conversation about the means they would use when considering suicide, and is one of the most important steps to preventing suicide, says Marshall.

"If you ask what kinds of thoughts you're having, they may tell you the means," she says.

If they don't volunteer that information, it's worth asking them directly, she adds. Once they say what means they have thought of using, one can discuss with them how to limit their access to it.

"The more time and space you can put between the person and harming themselves, the better," says Marshall. "If this is someone who is a firearm owner, you may talk with them to make sure they don't have ready access to firearm in moments of crisis."

8. Help them tackle the mental health care system

When someone is in urgent crisis mode, it's often not the best time to try to navigate the mental health care system, says DeGolier. But to prevent a future crisis, offer to help your loved one connect with a mental health professional to find out whether medications can help them and to learn ways to manage their mood and suicidal thinking.

A kind of talk therapy called dialectical behavior therapy, or DBT, has been shown to be effective in reducing risk of suicide. It teaches people strategies to calm their minds and distract themselves when the suicidal thoughts surface.

One bright side of the pandemic is that mental health providers are doing most appointments virtually, so it has expanded access to care for many.

Still, it can be hard for someone who's struggling with negative emotions to get and keep a mental health appointment. Family members and friends can help, notes Whiteside.

"Know that it takes persistence," she says. "You don't stop until you have an appointment for them. That may mean you call 30 people until you find someone who has an availability. You take the day off from work, go with them."

Lezine says he was fortunate to have had that kind of help and support from his college friend when he was struggling.

"One of the things that was helpful ... was she went with me [to my appointment]," he says. "When you're feeling really down and feeling like you don't matter as much, you might not want to take time, or think that it's worth the time, or feel like 'I don't want to go through this.' "

Many people don't make it to their first appointment, or don't follow up, he says. Having a person hold your hand through the process, accompany you to your appointments can prevent that. This can be hard during the pandemic but get creative: Offer to drive there separately and wait nearby for them, or accompany them by video call while they wait.

"It does make a difference, making you feel like you have another person who cares," says Lezine.

9. Explore tools and support online

For those struggling to access mental health care, there are some evidence-based digital tools that can also help.

For example, there's a smartphone app called Virtual Hope Box, which is modeled on cognitive behavioral therapy techniques. Research shows that veterans who were feeling suicidal and used the app were able to cope better with negative emotions.

Whiteside and her colleagues started a website called Now Matters Now, which offers videos with personal stories of suicide survivors talking about their own struggles and how they have overcome their suicidal thoughts. Stories of survival and coping with suicidal thoughts have been shown to have a positive effect on people at risk of suicide.

The website also has videos that teach some simple skills that are otherwise taught by a therapist trained to offer DBT.

Those skills include mindfulness and paced breathing, which involves breathing with exhales that last longer than the inhales. Whiteside explains that this can calm the nervous system. Similarly, a cold shower or splashing ice water on one's face or making eye contact with someone can distract and/or calm the person who is at immediate risk of taking their own life.

Surveys show that people who visit the website and watch the videos have a short-term reduction in their suicidal thoughts, she says.

Inner Critic vs. Inner Coach

988

What I Do When I Make Mistakes

Reactive vs. Proactive

Foundations of Self Love

Talk To Yourself As You Would...

How To Sit With Discomfort

Your Brain on Music

Your Brain on Music

A popular class breaks down how our brains respond to music.

Since 2006, two UCF professors — neuroscientist Kiminobu Sugaya and world-renowned violinist Ayako Yonetani — have been teaching one of the most popular courses in The Burnett Honors College. “Music and the Brain” explores how music impacts brain function and human behavior, including by reducing stress, pain and symptoms of depression as well as improving cognitive and motor skills, spatial-temporal learning and neurogenesis, which is the brain’s ability to produce neurons. Sugaya and Yonetani teach how people with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s also respond positively to music.

“Usually in the late stages, Alzheimer’s patients are unresponsive,” Sugaya says. “But once you put in the headphones that play [their favorite] music, their eyes light up. They start moving and sometimes singing. The effect lasts maybe 10 minutes or so even after you turn off the music.”

This can be seen on an MRI, where “lots of different parts of the brain light up,” he says. We sat down with the professors, who are also husband and wife, and asked them to explain which parts of the brain are activated by music.

WHAT MUSIC IS THE BEST?

Turns out, whether it’s rock ‘n’ roll, jazz, hip-hop or classical, your gray matter prefers the same music you do. “It depends on your personal background,” Yonetani says. For a while, researchers believed that classical music increased brain activity and made its listeners smarter, a phenomenon called the Mozart effect. Not necessarily true, say Sugaya and Yonetani. In recent studies, they’ve found that people with dementia respond better to the music they grew up listening to. “If you play someone’s favorite music, different parts of the brain light up,” Sugaya explains. “That means memories associated with music are emotional memories, which never fade out — even in Alzheimer’s patients.”

MUSIC CAN…

CHANGE YOUR ABILITY TO PRECEIVE TIME

TAP INTO PRIMAL FEAR

REDUCE SEIZURES

MAKE YOU A BETTER COMMUNICATOR

MAKE YOU STRONGER

BOOST YOUR IMMUNE SYSTEM

ASSIST IN REPAIRING BRAIN DAMAGE

MAKE YOU SMARTER

EVOKE MEMORIES

HELP PARKINSON’S PATIENTS

DID YOU KNOW?

USE IT OR LOSE IT We are all born with more neurons than we actually need. Typically by the age of 8, our brains do a major neuron dump, removing any neurons perceived as unnecessary, which is why it’s easier to teach language and music to younger children. “If you learn music as a child, your brain becomes designed for music,” Sugaya says.

OLDEST INSTRUMENT According to National Geographic, a 40,000-year-old vulture-bone flute is the world’s oldest musical instrument.

HAIRY CELLS The ear only has 3,500 inner hair cells, compared to the more than 100 million photoreceptors found in the eye. Yet our brains are remarkably adaptable to music.

SING ALONG In the Sesotho language, the verb for singing and dancing are the same (ho bina), as it is assumed the two actions occur together.

SEASONAL SONGBIRDS

Sugaya has also conducted neurological studies on songbirds. His research has found that “canaries stop singing every autumn when the brain cells responsible for song generation die.” However, the neurons grow back over the winter months, and the birds learn their songs over again in the spring. He takes this as a sign that “music may increase neurogenesis in the brain.”

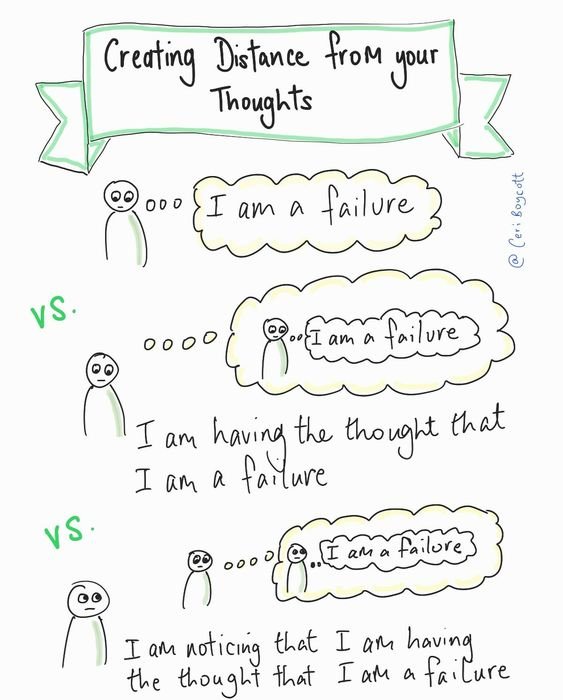

Creating Distance From Your Thoughts

Box Breathing

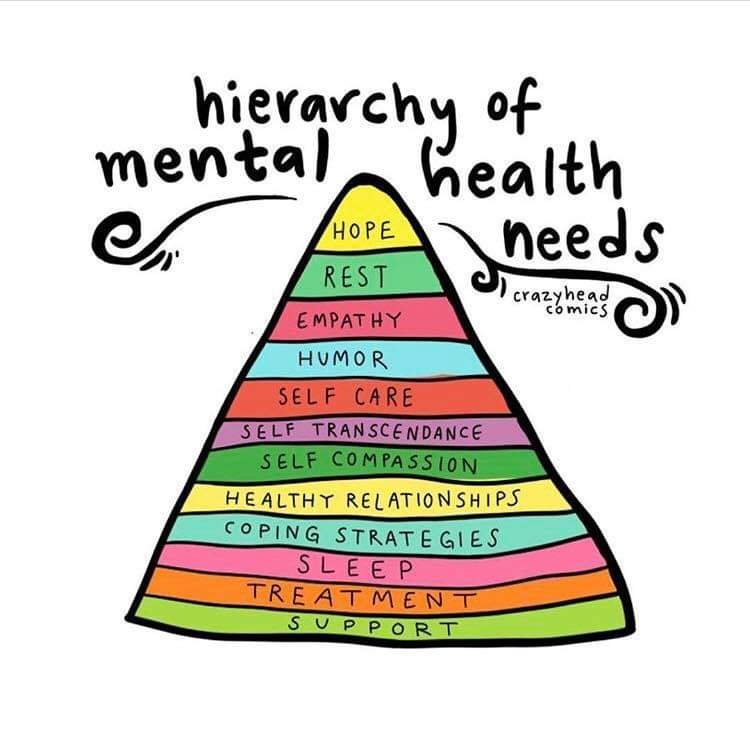

Hierarchy of Mental Health Needs

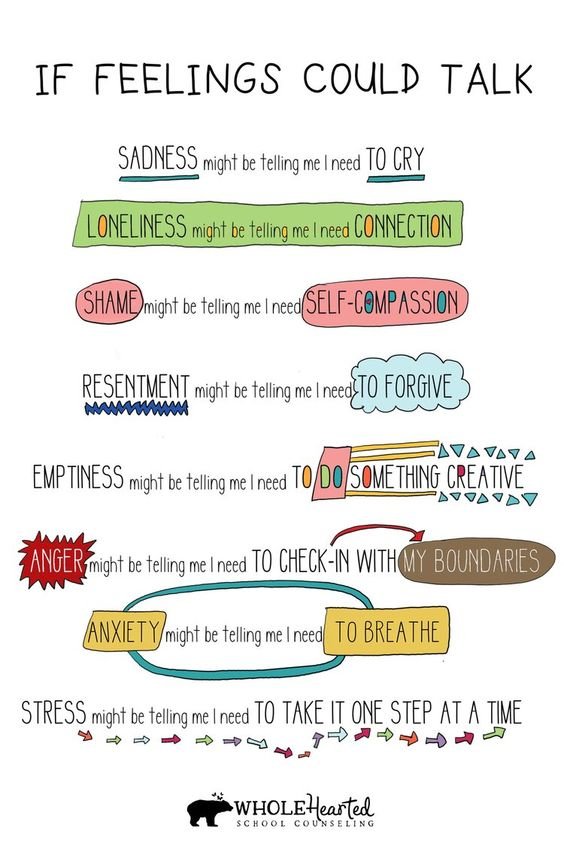

If Feelings Could Talk

Resilience

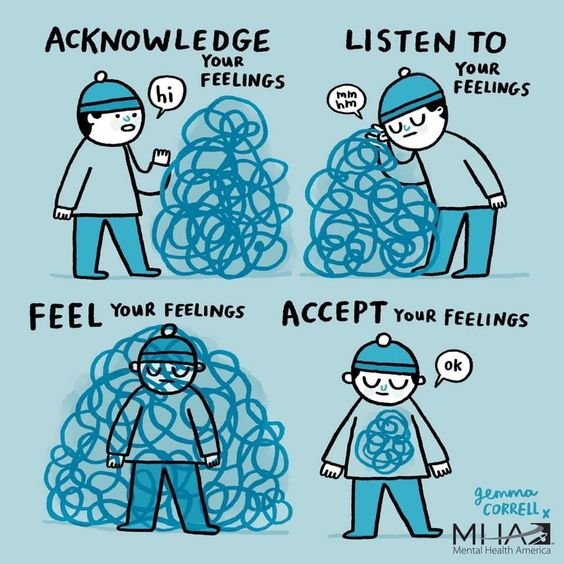

Accepting Your Feelings

Attachment Styles & Their Role in Relationships

Attachment Styles & Their Role in Relationships

Published on July 2, 2020 Updated on July 15, 2022

John Bowlby‘s work on attachment theory dates back to the 1950’s. Based on his theory, four adult attachment styles were identified: 1. anxious-preoccupied, 2. avoidant-dismissive , 3. disorganized / fearful-avoidant, and 4. secure.

Attachment styles develop early in life and often remain stable over time.

People with insecure attachment styles might have to put some intentional effort into resolving their attachment issues, in order to become securely attached.

What are attachment styles and how do they affect our relationships?

It’s human nature to seek contact and relationships, to seek love, support, and comfort in others. In fact, according to social psychologist Roy Baumeister, the ‘need to belong’ is one of the main forces that drives individuals.

From an evolutionary perspective, cultivating strong relationships and maintaining them has both survival and reproductive advantages. After all, most of us do ‘need to belong’ and do want closeness and intimacy in our lives.

Yet, love and relationships are rarely as perfect and problem-free as we would like them to be.

Have you noticed repeating patterns in your love life?

Maybe you have never really thought through or analyzed your behavior in relationships. Still, you might have noticed repeating patterns in your love life.

Have you wondered why you keep ending up in the same situation, even with different partners?

Do you get too clingy or jealous? Or do you always seem to be more involved than your partner? Maybe you want to be with someone, but as soon as things get emotionally intimate, you back off?

If you have noticed a pattern of unhealthy and emotionally challenging behaviors in your love life, you might benefit from digging deep and exploring the way you attach to people in intimate relationships. Here is where knowing about attachment theory comes in handy.

What is attachment theory?

Attachment theory has a long history and has been used as a basis for continuous research. The first step is to get acquainted with the basics and understand the different attachment styles.

According to psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby, one’s relationship with their parents during childhood has an overarching influence on their social, intimate relationships and even relationships at work in the future.

In other words, your early relationship with your caregivers sets the stage for how you will build relationships as an adult.

There are four adult attachment styles:

Anxious (also referred to as Preoccupied)

Avoidant (also referred to as Dismissive)

Disorganized (also referred to as Fearful-Avoidant)

Before getting into what characterizes the four groups, it might be useful to point out how attachment styles develop in children.

How do attachment styles develop in early childhood?

The behavior of the primary caregivers (usually one’s parents) contributes to and forms the way a child perceives close relationships.

The child is dependent on his or her caregivers and seeks comfort, soothing, and support from them. If the child’s physical and emotional needs are satisfied, he or she becomes securely attached.

This, however, requires that the caregivers offer a warm and caring environment and are attuned to the child’s needs, even when these needs are not clearly expressed.

Misattunement on the side of the parent, on the other hand, is likely to lead to insecure attachment in their children.

Each one of the four attachment styles has its typical traits and characteristics.

Yet, a person does not necessarily fit 100% into a single category: you may not match ‘the profile’ exactly.

The point of self-analysis is to identify unhealthy behaviors and understand what you might need to work on in order to improve your love life. So, let’s get to it!

How does each of the four attachment styles manifest in adults?

1. Anxious / Preoccupied

For adults with an anxious attachment style, the partner is often the ‘better half.’

The thought of living without the partner (or being alone in general) causes high levels of anxiety. People with this type of attachment typically have a negative self-image, while having a positive view of others.

The anxious adult often seeks approval, support, and responsiveness from their partner.

People with this attachment style value their relationships highly, but are often anxious and worried that their loved one is not as invested in the relationship as they are.

A strong fear of abandonment is present, and safety is a priority. The attention, care, and responsiveness of the partner appears to be the ‘remedy’ for anxiety.

On the other hand, the absence of support and intimacy can lead the anxious / preoccupied type to become more clinging and demanding, preoccupied with the relationship, and desperate for love.

2. Avoidant / Dismissive

The dismissing / avoidant type would often perceive themselves as ‘lone wolves’: strong, independent, and self-sufficient; not necessarily in terms of physical contact, but rather on an emotional level.

These people have high self-esteem and a positive view of themselves.

The dismissing / avoidant type tend to believe that they don’t have to be in a relationship to feel complete.

They do not want to depend on others, have others depend on them, or seek support and approval in social bonds.

Adults with this attachment style generally avoid emotional closeness. They also tend to hide or suppress their feelings when faced with a potentially emotion-dense situation.

3. Disorganized / Fearful-Avoidant

The disorganized type tends to show unstable and ambiguous behaviors in their social bonds.

For adults with this style of attachment, the partner and the relationship themselves are often the source of both desire and fear.

Fearful-avoidant people do want intimacy and closeness, but at the same time, experience troubles trusting and depending on others.

They do not regulate their emotions well and avoid strong emotional attachment, due to their fear of getting hurt.

4. Secure Attachment

The three attachment styles covered so far are insecure attachment styles.

They are characterized by difficulties with cultivating and maintaining healthy relationships.

In contrast, the secure attachment style implies that a person is comfortable expressing emotions openly.

Adults with a secure attachment style can depend on their partners and in turn, let their partners rely on them.

Relationships are based on honesty, tolerance, and emotional closeness.

The secure attachment type thrive in their relationships, but also don’t fear being on their own. They do not depend on the responsiveness or approval of their partners, and tend to have a positive view of themselves and others.

Where do you stand?

Now that you are acquainted with the four adult attachment styles, you probably have an idea of which one you lean towards.

It is completely normal to recognize features of different styles in your history of intimate relationships. Attachment styles can change with major life events, or even with different partners.

An insecurely attached individual could form a secure bond when they have a securely attached partner.

A person with a secure attachment style could, in contrast, develop an unhealthy relationship behavior after experiencing trauma or losing a loved one. So, there is no need to fit any specific profile.

Chances are that many of us don’t fully belong to the securely attached group.

Even if we think we have stable relationships, there might be patterns in our behavior that keep bothering us or keep making us stressed/unhappy. Unfortunately, some individuals will recognize themselves in one of the three insecure ‘profiles’ – the less healthy ones.

In that case, it is preferable and highly recommended that they address the issue actively and if necessary, seek individual psychological help.

But here’s the thing: this struggle is simply not necessary, as there are many ways to heal and recover from attachment disturbances.

Strongly expressed insecure and unstable attachment styles can cause anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues.

But here’s the thing: this struggle is simply not necessary, as there are many ways to heal and recover from attachment disturbances.