How to Deal with Task Paralysis

No, You are not...

Accept How You Feel...

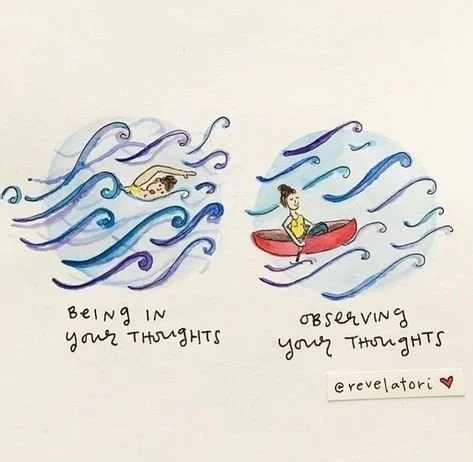

Observing Your Thoughts

What I Do When It Starts Getting Bad Again

Nurtured by Nature

Nurtured by nature

Psychological research is advancing our understanding of how time in nature can improve our mental health and sharpen our cognition

By Kirsten Weir Date created: April 1, 2020 12 min read

Be honest: How much time do you spend staring at a screen each day? For most Americans, that number clocks in at more than 10 hours, according to a 2016 Nielsen Total Audience Report. Our increasing reliance on technology, combined with a global trend toward urban living, means many of us are spending ever less time outdoors—even as scientists compile evidence of the value of getting out into the natural world.

From a stroll through a city park to a day spent hiking in the wilderness, exposure to nature has been linked to a host of benefits, including improved attention, lower stress, better mood, reduced risk of psychiatric disorders and even upticks in empathy and cooperation. Most research so far has focused on green spaces such as parks and forests, and researchers are now also beginning to study the benefits of blue spaces, places with river and ocean views. But nature comes in all shapes and sizes, and psychological research is still fine-tuning our understanding of its potential benefits. In the process, scientists are charting a course for policymakers and the public to better tap into the healing powers of Mother Nature.

“There is mounting evidence, from dozens and dozens of researchers, that nature has benefits for both physical and psychological human wellbeing,” says Lisa Nisbet, PhD, a psychologist at Trent University in Ontario, Canada, who studies connectedness to nature. “You can boost your mood just by walking in nature, even in urban nature. And the sense of connection you have with the natural world seems to contribute to happiness even when you’re not physically immersed in nature.”

Cognitive benefits

Spending time in nature can act as a balm for our busy brains. Both correlational and experimental research have shown that interacting with nature has cognitive benefits—a topic University of Chicago psychologist Marc Berman, PhD, and his student Kathryn Schertz explored in a 2019 review. They reported, for instance, that green spaces near schools promote cognitive development in children and green views near children’s homes promote self-control behaviors. Adults assigned to public housing units in neighborhoods with more green space showed better attentional functioning than those assigned to units with less access to natural environments. And experiments have found that being exposed to natural environments improves working memory, cognitive flexibility and attentional control, while exposure to urban environments is linked to attention deficits (Current Directions in Psychological Science, Vol. 28, No. 5, 2019).

Researchers have proposed a number of ideas to explain such findings, as Nisbet and colleagues described in a review of the benefits of connection with nature (Capaldi, C.A., et al., International Journal of Wellbeing, Vol. 5, No. 4, 2015). The biophilia hypothesis argues that since our ancestors evolved in wild settings and relied on the environment for survival, we have an innate drive to connect with nature. The stress reduction hypothesis posits that spending time in nature triggers a physiological response that lowers stress levels. A third idea, attention restoration theory, holds that nature replenishes one’s cognitive resources, restoring the ability to concentrate and pay attention.

The truth may be a combination of factors. “Stress reduction and attention restoration are related,” Nisbet points out. “And because of the societal problems we’re dealing with in terms of stress, both of these theories have gotten a lot of attention from researchers.”

Experimental findings show how impressive nature’s healing powers can be—just a few moments of green can perk up a tired brain. In one example, Australian researchers asked students to engage in a dull, attention-draining task in which they pressed a computer key when certain numbers flashed on a screen. Students who looked out at a flowering green roof for 40 seconds midway through the task made significantly fewer mistakes than students who paused for 40 seconds to gaze at a concrete rooftop (Lee, K.E., et al., Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol. 42, No. 1, 2015).

Even the sounds of nature may be recuperative. Berman and colleagues found that study participants who listened to nature sounds like crickets chirping and waves crashing performed better on demanding cognitive tests than those who listened to urban sounds like traffic and the clatter of a busy café (Van Hedger, S.C., et. al., Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, Vol. 26, No. 2, 2019).

Nature and happiness

While such laboratory experiments are intriguing, they don’t fully capture the diverse benefits that go hand in hand with time spent in the outdoor world, says Cynthia Frantz, PhD, a professor of psychology and environmental studies at Oberlin College in Ohio. “Spending time in nature has cognitive benefits, but it also has emotional and existential benefits that go beyond just being able to solve arithmetic problems more quickly,” she notes.

In a review of the research, Gregory Bratman, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of Washington, and colleagues shared evidence that contact with nature is associated with increases in happiness, subjective well-being, positive affect, positive social interactions and a sense of meaning and purpose in life, as well as decreases in mental distress (Science Advances, Vol. 5, No. 7, 2019).

Other work suggests that when children get outside, it leaves a lasting impression. In a study of residents of Denmark, researchers used satellite data to assess people’s exposure to green space from birth to age 10, which they compared with longitudinal data on individual mental health outcomes. The researchers examined data from more than 900,000 residents born between 1985 and 2003. They found that children who lived in neighborhoods with more green space had a reduced risk of many psychiatric disorders later in life, including depression, mood disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders and substance use disorder. For those with the lowest levels of green space exposure during childhood, the risk of developing mental illness was 55% higher than for those who grew up with abundant green space (Engemann, K., et al., PNAS, Vol. 116, No. 11, 2019).

There is even evidence that images of nature can be beneficial. Frantz and colleagues compared outcomes of people who walked outside in either natural or urban settings with those of people who watched videos of those settings. They found that any exposure to nature—in person or via video—led to improvements in attention, positive emotions and the ability to reflect on a life problem. But the effects were stronger among those who actually spent time outside (Mayer, F.S., et al., Environment and Behavior, Vol. 41, No. 5, 2009).

More recently, scientists have begun exploring whether virtual reality nature experiences are beneficial. In a review of this work, Mathew White, PhD, an environmental psychologist at the University of Exeter in England, and colleagues concluded that while the real deal is best, virtual reality can be a worthwhile substitute for people who are unable to get outdoors, such as those with mobility problems or illness (Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Vol. 14, 2018).

Nature might also make us nicer—to other people as well as to the planet. John Zelenski, PhD, a professor of psychology at Carleton University in Ontario, Canada, and colleagues showed undergraduates either nature documentaries or videos about architectural landmarks. Then the participants played a fishing game in which they made decisions about how many fish to harvest across multiple seasons. Those who had watched the nature video were more likely to cooperate with other players, and also more likely to make choices that would sustain the fish population (Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol. 42, No. 1, 2015). In another experiment, Zelenski and his colleagues found that elementary school children acted more prosocially to classmates and strangers after a field trip to a nature school than they did after a visit to an aviation museum (Dopko, R.L., et al., Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol. 63, No. 1, 2019).

Those generous behaviors weren’t attributed to students’ moods, Zelenski and his colleagues found, so it wasn’t simply that spending time in nature made them happier and therefore more giving. Another plausible (though unproven) explanation is the emotion of awe. “There are some hints that awe is associated with generosity, and nature can be a way to induce awe,” he says. “One of the things that may come from awe is the feeling that the individual is part of a much bigger whole.”

Experience vs. connection

With so many benefits linked to nature, people naturally wonder: How much time outside is enough? White and colleagues took a stab at answering that question by studying a representative sample of nearly 20,000 adults across the United Kingdom. They found people who had spent at least two recreational hours in nature during the previous week reported significantly greater health and well-being. That pattern held true across subgroups including older adults and people with chronic health problems, and the effects were the same whether they got their dose of nature in a single 120-minute session or spread out over the course of the week (Scientific Reports, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2019). “We’re not saying we’ve cracked this nut yet, but this is a first step toward making specific recommendations about how much time in nature is enough,” White says.

The amount of time one spends in nature isn’t the only element to consider—it’s also beneficial to feel connected to the natural world even when you’re stuck at a desk. Researchers call this feeling by a variety of names, including nature relatedness, connectedness to nature and inclusion of nature in self, and they’ve developed a number of scales to measure the trait.

Whatever you call it, connectedness to nature seems to benefit mood and mental health. In a meta-analysis, Alison Pritchard, PhD, ABPP, at the University of Derby in England, and colleagues found that people who feel more connected to nature have greater eudaimonic well-being—a type of contentment that goes beyond just feeling good and includes having meaningful purpose in life (Journal of Happiness Studies, online first publication, 2019).

Zelenski and Nisbet studied whether connection itself is the magic ingredient. They assessed the overlap between connectedness with nature and a general sense of connectedness, such as feeling in tune with one’s friends or community. They found that feeling connected to nature was a significant predictor of happiness even after controlling for the effects of general connectedness (Environment and Behavior, Vol. 46, No. 1, 2014). “People who feel that their self-concept is intertwined with nature report being a bit happier,” says Zelenski. “Nature connectedness isn’t the biggest predictor of happiness, but [the association between the two] is quite consistent.”

In fact, nature might help to buffer the effects of loneliness or social isolation. White and his colleagues surveyed 359 U.K. residents about their social connectedness and proximity to nature over the previous week. Social isolation is typically associated with worse subjective well-being. But the researchers found that when people with low social connectedness had high levels of nearby nature, they reported high levels of wellbeing (Cartwright, B.D.S., et al., International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 15, No. 6, 2018). “There are people who don’t necessarily want to spend their time with others, but they feel connected to the natural environment, and that can enhance their well-being,” White says.

Green and blue spaces

It’s clear that getting outside is good for us. Now, scientists are working to determine what types of environments are best. Much attention has gone to green spaces, but White has studied a variety of marine and freshwater environments and found these blue spaces are also good for well-being (Gascon, M., et al., International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, Vol. 220, No. 8, 2017.) In fact, he says, they may even be slightly more restorative than green spaces.

There may also be value in trekking to remote locations. In a survey of 4,515 U.K. residents, White found that people reported more connection to nature and felt more restored after visiting rural and coastal locations than they did after spending time in urban green spaces. Areas deemed to be “high environmental quality”—such as nature reserves and protected habitats—were also more beneficial than areas with low biodiversity (Wyles, K.J., et al., Environment and Behavior, Vol. 51, No. 2, 2019). In other work, White and his colleagues found that people who watched nature videos with a diverse mix of flora and fauna reported lower anxiety, more vitality and better mood than those who watched videos featuring less biodiverse landscapes (Wolf, L.J., et al., PLOS ONE, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2017).

But there’s an important caveat, White adds: “If you have a break from work and you’ve only got half an hour, then a wild remote place is no use to you at all.” Urban parks and trees also produce positive outcomes. Just like a little exercise is better than none, we should take advantage of green and blue spaces wherever and whenever we can. That’s easier said than done, though, especially for people at a socioeconomic disadvantage. Poorer neighborhoods, White notes, are seldom the ones with leafy groves and ocean views.

Yet policymakers, city planners, environmental organizations and government agencies are coming around to the importance of natural spaces, and psychologists are offering them their expertise, says White, who has presented his research to groups such as the U.K.’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Organizations and cities are expressing interest in this research, Zelenski says, though many policymakers are waiting to see the results of intervention studies before investing in green infrastructure. One of the United Nations’ sustainable development goals includes the target of providing universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible green and public spaces by 2030.

There is urgency in fostering these connections, says Nisbet. Because while people benefit from their connection with the natural world, the environment also benefits when people feel connected and committed to caring for the Earth—and between climate change and habitat loss, the planet is in serious need of some care. “When people are disconnected from nature, they aren’t motivated to work on wicked problems like climate change. We’re losing the environments that contribute to our flourishing,” she says. “The key question is, How do we help people feel connected to nature so we’re motivated to protect the places that will help us thrive?”

Key points

Spending time in nature is linked to both cognitive benefits and improvements in mood, mental health and emotional well-being.

Feeling connected to nature can produce similar benefits to well-being, regardless of how much time one spends outdoors.

Both green spaces and blue spaces (aquatic environments) produce well-being benefits. More remote and biodiverse spaces may be particularly helpful, though even urban parks and trees can lead to positive outcomes.

'Bad' Behavior Iceberg

Instead of "How Are You?"

Physical Symptoms of Panic Attacks

How Trauma Therapy Works

Note to Self

How to Protect Yourself Against People's Negative Moods

How to Protect Yourself Against People's Negative Moods

10 tips to prevent other people from bringing you down.

Posted January 9, 2023 | Susanna Newsonen

KEY POINTS

Other people's negativity is not yours to carry—or to fix.

Remove judgment from the situation and accept the mood for what it is: a temporary feeling.

Protect yourself with self-care, by setting boundaries, and by practicing your own inner calm.

Being human means you get to experience all kinds of moods—the good, the bad, and everything in between. Being human also means you are influenced by other people's moods—the good, the bad, and everything in between. The challenge is not letting the bad get to you. Yes, you want to be there for your people and help them if you can. But, you don't want your mood to be taken down by them. You have to think of your well-being and mental health first.

That's why you need to create a protective bubble around you so that you're less affected by other people's negative moods. Here is how:

1. Acknowledge that their negativity is not yours to carry.

There is a clear separation between them and you, and their mood and your mood. Acknowledge this. Just because they are having a bad day doesn't mean you have to have one too. Say to yourself, This is not my emotion and I don't have to take it on.

2. Recognize that their negativity is not yours to fix.

Just like someone else's mood is not your responsibility to carry, it's also not your responsibility to fix. Often we get too involved in other people's emotions, especially when they are loved ones we want to help. The reality is that moods can only be changed by the person carrying them. Their mood is something beyond your control, and accepting this is the first step in feeling less frustrated by it.

3. Accept the mood for what it is: a temporary, fleeting feeling.

We all have good days and bad days. The more you judge someone else's bad ones, the more susceptible you become to them. Remove judgment from the equation and remind yourself that it is simply how they're feeling at this moment in time. It's OK, and it will pass. Remind yourself of the times when they are in a good mood and focus on making the most of those. However, if this person's negative mood is a reoccurring challenge for you, check out tip six.

article continues after advertisement

4. Listen to their complaints—but don't join in on them.

You can be an empathetic listener without joining in on the misery. Most people who are struggling aren't expecting you to solve their problems but are simply hoping to feel understood. Simply letting them voice their concerns can help them to bring their mood to a better place. The key is not to fuel them. Nod your head and say things like, "I hear you"; "I understand your frustration"; and "That sounds tough" without getting involved. Whatever you do, do not join in on the negativity. It will simply fuel the flames and take you with them.

5. Take responsibility for your mood.

As much as emotions and moods can be contagious, you are still responsible for yours. If someone's negative mood is bringing you down, take positive action. Change the situation or how you're responding to it. Share an empathetic smile. Take a few deep breaths. Give them words of encouragement or a compliment. Share some good news. Finish a relevant sentence that starts with, "Isn't it amazing that....?" Do what you need to do to put yourself back into a good place.

6. Set healthy boundaries.

If a coworker who is always moaning about their job approaches you for another rant, simply tell them you haven't got the time for it. If a friend continues to complain about how envious they are of your good life, tell them you worked hard to get it and they can too. If a family member keeps expecting you to solve a historical petty grudge with someone else, tell them you don't have the energy for it. Set boundaries, speak up when you feel taken advantage of, and ask for what you need.

7. Inhale good vibes, exhale bad vibes.

Taking a few deep breaths whilst focusing on what you're inhaling and exhaling can do wonders. When you inhale for at least four seconds, smile inwardly as you imagine yourself taking in all the positive energy there is. With every inhale, focus on a word and say it to yourself, like calm, safety, hope, gratitude, or joy. When you exhale for another four seconds, open your mouth wide and exhale loudly as you imagine all the nasty things coming out of your body and mind. Express a word every time you exhale, such as stress, negativity, overwhelm, or disappointment. Keep doing this until you feel your nervous system calming down.

article continues after advertisement

8. Practice grounding activities.

The more practice you have in finding and keeping your inner calm, the less likely you are to be affected by other people's chaos. Different types of mindfulness practices help you to manage your emotions and mind, whilst certain types of bodily movement, like yoga and nature walks, help to ground the body. Focus on developing your inner calm rather than being frustrated by someone else's lack of it.

9. Take extra-good care of yourself.

You can only reach your maximum level of resilience when you are well-rested, well-fed, and feeling at least somewhat fulfilled. If you're not, you're much more susceptible to the negative moods around you and it will be harder than ever to fight them off. Practice self-care every single day.

10. Remove yourself from the situation.

You want to be there for your loved ones, but there may come a point when it feels too much for you to handle. If you start to spiral downward, excuse yourself. Say you need a moment to gather yourself. Go to the bathroom, go spend two minutes in the fresh air, drink some water, take some deep breaths, and remind yourself what you have to be grateful for. Only go back into the room when you feel you are resilient enough to handle what is there.

Emotions are Signals

Things I Didn't Know Were Anxiety

7 Resolutions for your Mental Health

Childhood Stress: How Parents Can Help

Childhood Stress: How Parents Can Help

Reviewed by: D'Arcy Lyness, PhD

All kids and teens feel stressed at times. Stress is a normal response to changes and challenges. And life is full of those — even during childhood.

We tend to think of stress as a bad thing, caused by bad events. But upcoming good events (like graduations, holidays, or new activities) also can cause stress.

Kids and teens feel stress when there’s something they need to prepare for, adapt to, or guard against. They feel stress when something that matters to them is at stake. Change often prompts stress — even when it’s a change for the better.

Stress has a purpose. It’s a signal to get ready.

When Can Stress Be Helpful?

In small amounts, and when kids have the right support, stress can be a positive boost. It can help kids rise to a challenge. It can help them push toward goals, focus their effort, and meet deadlines. This kind of positive stress allows kids to build the inner strengths and skills known as resilience.

When Can Stress Be Harmful?

Stress or adversity that is too intense, serious, long-lasting, or sudden can overwhelm a child’s ability to cope. Stress can be harmful when kids don’t have a break from stress, or when they lack the support or the coping skills they need. Over time, too much stress can affect kids’ mental and physical health.

As a parent you can’t prevent your children from feeling stress. But you can help kids and teens cope. You can:

Help them use positive stress to go for goals, adapt to changes, face challenges, and gain confidence.

Give extra support and stability when they go through stressful life events.

Protect them from the harmful effects of too much stress, such as chronic stress and traumatic stress.

What Is Positive Stress?

Positive stress is the brief stress kids and teens feel when they face a challenge. It can prompt them to prepare and focus. It can motivate them to go for goals, get things done, or try new things. They might feel positive stress before a test, a big game, or a recital. When they face the challenge, the stress is over.

Positive stress gives kids the chance to grow and learn.

Here’s an example: The everyday pressure to get to school on time prompts kids to get their shoes on, gather their things, and head for the bus. But if kids don’t know how to use that positive stress, or don’t yet have the coping skills they need, it could mean a hectic race to the bus that leaves both parents and kids upset.

What parents can do: When it comes to handling that morning school prep (or any other moment of normal stress), it's tempting to step in and get everything ready for your child. But that won’t help kids learn how to use positive stress. Instead, teach kids how to prepare without doing it for them. This takes more time and patience, but it’s worth it.

This type of positive stress can prompt kids to adapt and gain coping skills they need. It can prepare them to handle life’s bigger challenges and opportunities.

What Is Life Event Stress?

Difficult Life Events

Many kids and teens face difficult life events or adversity. Some get sick or need a hospital stay. Some have parents who split up. Some face the death of a loved one, move to a new neighborhood, or start a new school. Any of these life events can cause stress.

When kids face difficult life events, they might feel stress on and off for a few days or weeks as they adjust.

What parents can do: Parents can provide extra support and stability. Listen and talk with your child. Help them feel safe and loved. If possible, let them know what to expect. Talk over what will happen, what they can do to cope, and how you’ll help. Give comfort and show caring. Set up simple routines to help them feel settled.

Good Life Events

Even life events that we think of as good can be stressful. A big birthday, the first day of a school year, graduation, holidays, or travel can prompt kids and teens to feel stress.

What parents can do: Parents can help kids and teens prepare for what’s ahead. Talk them through the situation, focusing on the positive parts. Give kids a say in the plans when possible. Listen to what they think and how they feel. If they feel stressed, let them know it’s OK and they can cope. You’ll be there for them as needed.

What Is Chronic Stress?

When difficult life events lead to stress that lasts for more than a few weeks, it’s called chronic stress. Chronic stress is hard on kids when they don’t have a break from it or when they don’t have the support they need or coping skills to offset the stress.

Having a serious health condition that lasts for a long time can lead to chronic stress. So can losing a parent or close family member or going through lasting adversity. Over time, stress like this can affect kids’ and teens’ mental and physical health. But there are things that can prevent the harmful effects of chronic stress.

What parents can do:

Help kids feel safe, loved, and cared for. This is the best way to offset stress. Feeling close to you and knowing you love and accept them is more important than ever. Provide routines, like the same bedtime, eating a meal together, or being there after school. Routines provide a rhythm and let kids know there are things they can count on.

Teach coping skills. Kids feel better when they know there are things they can do for themselves to offset their stress. Kids of all ages can learn and practice calm breathing and meditation. There are many other skills to learn too.

Help them take a break from stress. Make time to play, draw or paint, spend time in nature, read a book, play an instrument, be with friends and family. These activities are more than just fun. They help kids and teens feel positive emotions that offset stress.

What Is Traumatic Stress?

This is the stress that comes with trauma events that are serious, intense, or sudden. Traumas such as serious accidents or injuries, abuse, or violence can prompt this type of stress.

Parents can step in to protect kids when they know they are being mistreated or bullied. But it’s not always possible to protect kids from every type of trauma. If kids and teens go through traumatic stress, parents can help them get the care they need to recover.

What parents can do:

Give kids and teens extra support and care. Be there to listen and talk. Let kids know that they are safe. Validate and accept their feelings. Let them know that, with time, they will feel better.

Reach out to your child’s doctor or a therapist. Some need therapy to heal from traumatic stress. Parents can take part in the therapy and learn how to best help their child.

Spend positive time together. Encourage kids and teens to do things they enjoy. These might be things you can do together or things your teen does on their own, like enjoying music, nature, or art. These things prompt positive emotions that can offset some of the stress left over from trauma.

Give kids and teens a chance to use their strengths in everyday life. Trauma and stress can leave them feeling vulnerable, anxious, or unsure of themselves. Knowing what they can do and who they are as a person can help kids and teens feel strong and confident.