What To Do When I Make A Mistake

The Storm Will Pass

Journal Prompts For Self Love

Drop Your Shoulders...

Reminders

Things To Not Feel Guilty For

New Month, New Beginning.

When You Feel...

Self Discovery Journal Prompts

How Do You Really Feel?

Making New Friends at Any Age. It's Easier Than it Seems

Making New Friends at Any Age. It's Easier Than it Seems

Friendships may be hard to make as we get older, but we still can.

Posted April 9, 2023 | F. Diane Barth, L.C.S.W.

KEY POINTS

Making friends as we get older can be challenging.

Shifting your perspective on friendship can make it easier to make new friends as your life changes.

New relationships need time to develop into meaningful friendships.

You know that friendships are important. You probably have seen research showing that strong social connections can lower our risk of a variety of emotional and physical illnesses such as depression and high blood pressure. Yet research also shows that once you’re out of college, it becomes increasingly hard to make new friends.

But don't give up. It's actually not as hard as it seems to make new friends. It does, however, require a slight shift in perspective. And to make that shift, it's useful to understand the problem itself.

Why is it hard to make new friends as an adult?

The reasons are pretty basic. In college, there are lots of people your age all around you. You have a wide range of peers to choose from, and simple, straightforward ways to connect. When you graduate, you and your friends tend to go in different directions, but even when you stay in touch, it’s harder to find time to hang out or connect when you’re all taking on new jobs, a new apartment, new roommates, and new relationships.

Busy schedules also make it hard for adults to develop new friendships. You might have found some work buddies, but getting together for anything other than a drink after work is often complicated. You have other things going on in your life, and so do they. Personal relationships, children, and other commitments can interfere with the easy camaraderie of school friendships. My PT colleague Beverly Flaxington has written about this problem and has some great suggestions about what you can do about it.

But there’s something else going on, too.

One of the problems for many of us is our definition of friendship. Often, we think that friends should be soulmates. We’re looking for someone who understands us, who shares our values and ways of being in the world, who stimulates our thinking, joins us in having fun, and makes us feel better when we’re down. Most adult friendships, however, offer some, but not all of these functions.

Gary had been out of college for about five years. He had never felt like a particularly popular guy, but in college he’d had a group of friends that he did things with. Although they’d said they would stay in touch after graduation, it was hard, with their new jobs, new lives, and in some cases, new girl or boyfriends.

“I think of myself as an independent person,” he told me. “But I’m feeling really lonely these days. And it’s hard to find new friends.”

Gary had tried. He went out for a beer with someone from work and invited someone else to go to a hockey game with him.

“It was fine,” he said. “But it just seemed to end there. The guy who went with me to the hockey game invited me to go to another one. I did, and it was fun. But then another time I suggested we go to a movie, and he wasn’t interested. That’s not good. I’m looking for someone who I can do different things with.”

Different kinds of friends

I asked Gary if he preferred to stay home and feel lonely over going with this friend to sports events. He said that he liked being home, sometimes, but if he was lonely, he’d rather go with this guy. “So maybe he can be a friend for certain activities,” I said.

Gary was intrigued by that idea. “Are you saying that it could be good to have different kinds of friends?” he asked. “Like for different activities?”

It turned out that he already had some categories of new acquaintances. There was a woman at work who liked jazz, which Gary had been interested in for years. “She has a boyfriend who also likes that kind of music. Maybe they would go to concerts with me from time to time,” he said.

A tennis player, it hadn’t occurred to him that one of the people he frequently played against could also be a friend. “We don’t have a lot in common,” Gary said, “but we’re well-matched tennis opponents. And we talk sometimes between sets. I like him.”

As Gary broadened his definition of friendship, he also opened himself up to connecting with different kinds of people.

Changing expectations

As we go through different life stages, we often find that old friends are less available for a variety of reasons. Marjorie*, for instance, retired at the age of 65, but some of her friends were still working full-time and weren’t available to join her in her new, more relaxed life. She was still getting together with a group of friends for dinner or a glass of wine, but they couldn’t take a walk or go to the movies in the middle of the day.

She had always been a busy woman who was engaged in many different activities. Retirement gave her an opportunity to do more volunteer work, play tennis, take pilates more regularly, and read all of the books on her very long reading list. She also took a pottery class, which she enjoyed so much that she became a regular at the pottery studio.

One day she told me, “You know, the other day I realized that even though I’m not spending more time with my old friends, I’m never lonely. I’ve met all kinds of interesting people through my activities, and I go out for coffee or lunch with some of them on occasion. In the past, I don’t think I would have called these new acquaintances friends, because I don’t share deep thoughts or feelings with them, which is what I always expect to do with friends. But maybe I expect something different from friends these days.”

I asked Marjorie if she could explain what that might be. “I think I expect some friends to be able to share the deeper stuff with me,” she said after thinking for a few moments. “But I think other qualities can also be what makes a person a friend. Like enjoying an activity together or sharing ideas about future activities. We don’t always have to be talking about feelings, which is what I’ve usually expected. I realized that that kind of relationship takes time to develop. Maybe eventually some of these newer connections will deepen into what I have with my old friends, but it isn’t necessary.”

Changing both your definition and your expectations of friendship can make it easier to find and develop new relationships as you get older. Understanding that new friendships will have a different texture and quality from old ones, and giving new relationships time and space to develop, can make it easier to find new friends.

Wheel of Coping

Nice Things You Can Do For Yourself

How to Deal with Task Paralysis

No, You are not...

Accept How You Feel...

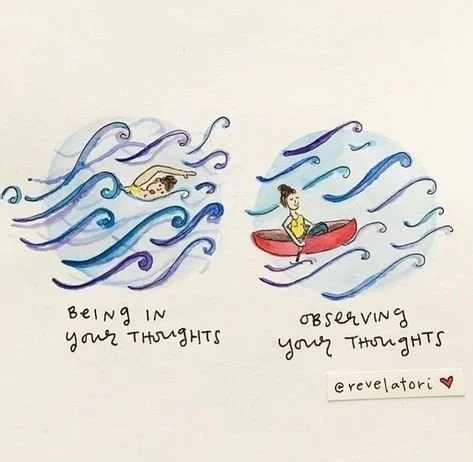

Observing Your Thoughts

What I Do When It Starts Getting Bad Again

Nurtured by Nature

Nurtured by nature

Psychological research is advancing our understanding of how time in nature can improve our mental health and sharpen our cognition

By Kirsten Weir Date created: April 1, 2020 12 min read

Be honest: How much time do you spend staring at a screen each day? For most Americans, that number clocks in at more than 10 hours, according to a 2016 Nielsen Total Audience Report. Our increasing reliance on technology, combined with a global trend toward urban living, means many of us are spending ever less time outdoors—even as scientists compile evidence of the value of getting out into the natural world.

From a stroll through a city park to a day spent hiking in the wilderness, exposure to nature has been linked to a host of benefits, including improved attention, lower stress, better mood, reduced risk of psychiatric disorders and even upticks in empathy and cooperation. Most research so far has focused on green spaces such as parks and forests, and researchers are now also beginning to study the benefits of blue spaces, places with river and ocean views. But nature comes in all shapes and sizes, and psychological research is still fine-tuning our understanding of its potential benefits. In the process, scientists are charting a course for policymakers and the public to better tap into the healing powers of Mother Nature.

“There is mounting evidence, from dozens and dozens of researchers, that nature has benefits for both physical and psychological human wellbeing,” says Lisa Nisbet, PhD, a psychologist at Trent University in Ontario, Canada, who studies connectedness to nature. “You can boost your mood just by walking in nature, even in urban nature. And the sense of connection you have with the natural world seems to contribute to happiness even when you’re not physically immersed in nature.”

Cognitive benefits

Spending time in nature can act as a balm for our busy brains. Both correlational and experimental research have shown that interacting with nature has cognitive benefits—a topic University of Chicago psychologist Marc Berman, PhD, and his student Kathryn Schertz explored in a 2019 review. They reported, for instance, that green spaces near schools promote cognitive development in children and green views near children’s homes promote self-control behaviors. Adults assigned to public housing units in neighborhoods with more green space showed better attentional functioning than those assigned to units with less access to natural environments. And experiments have found that being exposed to natural environments improves working memory, cognitive flexibility and attentional control, while exposure to urban environments is linked to attention deficits (Current Directions in Psychological Science, Vol. 28, No. 5, 2019).

Researchers have proposed a number of ideas to explain such findings, as Nisbet and colleagues described in a review of the benefits of connection with nature (Capaldi, C.A., et al., International Journal of Wellbeing, Vol. 5, No. 4, 2015). The biophilia hypothesis argues that since our ancestors evolved in wild settings and relied on the environment for survival, we have an innate drive to connect with nature. The stress reduction hypothesis posits that spending time in nature triggers a physiological response that lowers stress levels. A third idea, attention restoration theory, holds that nature replenishes one’s cognitive resources, restoring the ability to concentrate and pay attention.

The truth may be a combination of factors. “Stress reduction and attention restoration are related,” Nisbet points out. “And because of the societal problems we’re dealing with in terms of stress, both of these theories have gotten a lot of attention from researchers.”

Experimental findings show how impressive nature’s healing powers can be—just a few moments of green can perk up a tired brain. In one example, Australian researchers asked students to engage in a dull, attention-draining task in which they pressed a computer key when certain numbers flashed on a screen. Students who looked out at a flowering green roof for 40 seconds midway through the task made significantly fewer mistakes than students who paused for 40 seconds to gaze at a concrete rooftop (Lee, K.E., et al., Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol. 42, No. 1, 2015).

Even the sounds of nature may be recuperative. Berman and colleagues found that study participants who listened to nature sounds like crickets chirping and waves crashing performed better on demanding cognitive tests than those who listened to urban sounds like traffic and the clatter of a busy café (Van Hedger, S.C., et. al., Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, Vol. 26, No. 2, 2019).

Nature and happiness

While such laboratory experiments are intriguing, they don’t fully capture the diverse benefits that go hand in hand with time spent in the outdoor world, says Cynthia Frantz, PhD, a professor of psychology and environmental studies at Oberlin College in Ohio. “Spending time in nature has cognitive benefits, but it also has emotional and existential benefits that go beyond just being able to solve arithmetic problems more quickly,” she notes.

In a review of the research, Gregory Bratman, PhD, an assistant professor at the University of Washington, and colleagues shared evidence that contact with nature is associated with increases in happiness, subjective well-being, positive affect, positive social interactions and a sense of meaning and purpose in life, as well as decreases in mental distress (Science Advances, Vol. 5, No. 7, 2019).

Other work suggests that when children get outside, it leaves a lasting impression. In a study of residents of Denmark, researchers used satellite data to assess people’s exposure to green space from birth to age 10, which they compared with longitudinal data on individual mental health outcomes. The researchers examined data from more than 900,000 residents born between 1985 and 2003. They found that children who lived in neighborhoods with more green space had a reduced risk of many psychiatric disorders later in life, including depression, mood disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders and substance use disorder. For those with the lowest levels of green space exposure during childhood, the risk of developing mental illness was 55% higher than for those who grew up with abundant green space (Engemann, K., et al., PNAS, Vol. 116, No. 11, 2019).

There is even evidence that images of nature can be beneficial. Frantz and colleagues compared outcomes of people who walked outside in either natural or urban settings with those of people who watched videos of those settings. They found that any exposure to nature—in person or via video—led to improvements in attention, positive emotions and the ability to reflect on a life problem. But the effects were stronger among those who actually spent time outside (Mayer, F.S., et al., Environment and Behavior, Vol. 41, No. 5, 2009).

More recently, scientists have begun exploring whether virtual reality nature experiences are beneficial. In a review of this work, Mathew White, PhD, an environmental psychologist at the University of Exeter in England, and colleagues concluded that while the real deal is best, virtual reality can be a worthwhile substitute for people who are unable to get outdoors, such as those with mobility problems or illness (Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Vol. 14, 2018).

Nature might also make us nicer—to other people as well as to the planet. John Zelenski, PhD, a professor of psychology at Carleton University in Ontario, Canada, and colleagues showed undergraduates either nature documentaries or videos about architectural landmarks. Then the participants played a fishing game in which they made decisions about how many fish to harvest across multiple seasons. Those who had watched the nature video were more likely to cooperate with other players, and also more likely to make choices that would sustain the fish population (Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol. 42, No. 1, 2015). In another experiment, Zelenski and his colleagues found that elementary school children acted more prosocially to classmates and strangers after a field trip to a nature school than they did after a visit to an aviation museum (Dopko, R.L., et al., Journal of Environmental Psychology, Vol. 63, No. 1, 2019).

Those generous behaviors weren’t attributed to students’ moods, Zelenski and his colleagues found, so it wasn’t simply that spending time in nature made them happier and therefore more giving. Another plausible (though unproven) explanation is the emotion of awe. “There are some hints that awe is associated with generosity, and nature can be a way to induce awe,” he says. “One of the things that may come from awe is the feeling that the individual is part of a much bigger whole.”

Experience vs. connection

With so many benefits linked to nature, people naturally wonder: How much time outside is enough? White and colleagues took a stab at answering that question by studying a representative sample of nearly 20,000 adults across the United Kingdom. They found people who had spent at least two recreational hours in nature during the previous week reported significantly greater health and well-being. That pattern held true across subgroups including older adults and people with chronic health problems, and the effects were the same whether they got their dose of nature in a single 120-minute session or spread out over the course of the week (Scientific Reports, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2019). “We’re not saying we’ve cracked this nut yet, but this is a first step toward making specific recommendations about how much time in nature is enough,” White says.

The amount of time one spends in nature isn’t the only element to consider—it’s also beneficial to feel connected to the natural world even when you’re stuck at a desk. Researchers call this feeling by a variety of names, including nature relatedness, connectedness to nature and inclusion of nature in self, and they’ve developed a number of scales to measure the trait.

Whatever you call it, connectedness to nature seems to benefit mood and mental health. In a meta-analysis, Alison Pritchard, PhD, ABPP, at the University of Derby in England, and colleagues found that people who feel more connected to nature have greater eudaimonic well-being—a type of contentment that goes beyond just feeling good and includes having meaningful purpose in life (Journal of Happiness Studies, online first publication, 2019).

Zelenski and Nisbet studied whether connection itself is the magic ingredient. They assessed the overlap between connectedness with nature and a general sense of connectedness, such as feeling in tune with one’s friends or community. They found that feeling connected to nature was a significant predictor of happiness even after controlling for the effects of general connectedness (Environment and Behavior, Vol. 46, No. 1, 2014). “People who feel that their self-concept is intertwined with nature report being a bit happier,” says Zelenski. “Nature connectedness isn’t the biggest predictor of happiness, but [the association between the two] is quite consistent.”

In fact, nature might help to buffer the effects of loneliness or social isolation. White and his colleagues surveyed 359 U.K. residents about their social connectedness and proximity to nature over the previous week. Social isolation is typically associated with worse subjective well-being. But the researchers found that when people with low social connectedness had high levels of nearby nature, they reported high levels of wellbeing (Cartwright, B.D.S., et al., International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 15, No. 6, 2018). “There are people who don’t necessarily want to spend their time with others, but they feel connected to the natural environment, and that can enhance their well-being,” White says.

Green and blue spaces

It’s clear that getting outside is good for us. Now, scientists are working to determine what types of environments are best. Much attention has gone to green spaces, but White has studied a variety of marine and freshwater environments and found these blue spaces are also good for well-being (Gascon, M., et al., International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, Vol. 220, No. 8, 2017.) In fact, he says, they may even be slightly more restorative than green spaces.

There may also be value in trekking to remote locations. In a survey of 4,515 U.K. residents, White found that people reported more connection to nature and felt more restored after visiting rural and coastal locations than they did after spending time in urban green spaces. Areas deemed to be “high environmental quality”—such as nature reserves and protected habitats—were also more beneficial than areas with low biodiversity (Wyles, K.J., et al., Environment and Behavior, Vol. 51, No. 2, 2019). In other work, White and his colleagues found that people who watched nature videos with a diverse mix of flora and fauna reported lower anxiety, more vitality and better mood than those who watched videos featuring less biodiverse landscapes (Wolf, L.J., et al., PLOS ONE, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2017).

But there’s an important caveat, White adds: “If you have a break from work and you’ve only got half an hour, then a wild remote place is no use to you at all.” Urban parks and trees also produce positive outcomes. Just like a little exercise is better than none, we should take advantage of green and blue spaces wherever and whenever we can. That’s easier said than done, though, especially for people at a socioeconomic disadvantage. Poorer neighborhoods, White notes, are seldom the ones with leafy groves and ocean views.

Yet policymakers, city planners, environmental organizations and government agencies are coming around to the importance of natural spaces, and psychologists are offering them their expertise, says White, who has presented his research to groups such as the U.K.’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Organizations and cities are expressing interest in this research, Zelenski says, though many policymakers are waiting to see the results of intervention studies before investing in green infrastructure. One of the United Nations’ sustainable development goals includes the target of providing universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible green and public spaces by 2030.

There is urgency in fostering these connections, says Nisbet. Because while people benefit from their connection with the natural world, the environment also benefits when people feel connected and committed to caring for the Earth—and between climate change and habitat loss, the planet is in serious need of some care. “When people are disconnected from nature, they aren’t motivated to work on wicked problems like climate change. We’re losing the environments that contribute to our flourishing,” she says. “The key question is, How do we help people feel connected to nature so we’re motivated to protect the places that will help us thrive?”

Key points

Spending time in nature is linked to both cognitive benefits and improvements in mood, mental health and emotional well-being.

Feeling connected to nature can produce similar benefits to well-being, regardless of how much time one spends outdoors.

Both green spaces and blue spaces (aquatic environments) produce well-being benefits. More remote and biodiverse spaces may be particularly helpful, though even urban parks and trees can lead to positive outcomes.