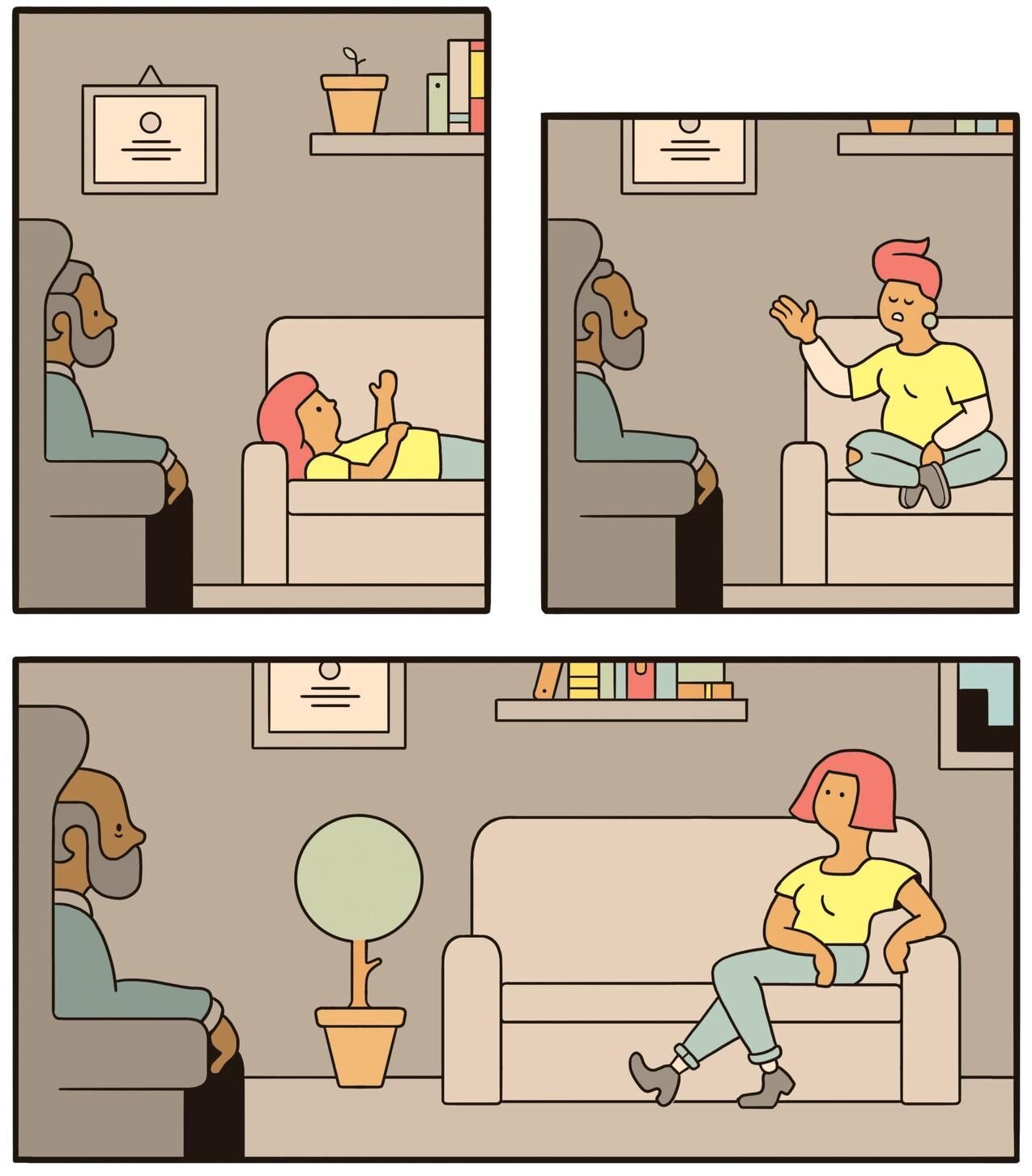

People in their 20s and 30s seek mental-health help more often, and they are changing the nature of treatment

Kristina, a 27-year-old publicist living in Manhattan, has been in and out of therapy since she was 9, when her parents got divorced. Back then, she says, “I had a pretty pragmatic view of what was happening, and so did my parents—going to therapy was just something you make kids of divorce do.” During her first year of college, Kristina (who requested that only her first name be used) suffered a sexual assault. Again, she says, therapy afterward was a given. “I figured I would use therapy to get through my trauma and then be done,” she says. “I eventually learned that’s not really how it works.” She has had four or five different therapists since then. So have most of her friends.

The stigma traditionally attached to psychotherapy has largely dissolved in the new generation of patients seeking treatment. Raised by parents who openly went to therapy themselves and who sent their children as well, today’s 20- and 30-somethings turn to therapy sooner and with fewer reservations than young people did in previous eras.

According to a 2017 report from the Center for Collegiate Mental Health at Penn State University, which compiled data from 147 colleges and universities, the number of students seeking mental-health help increased from 2011 to 2016 at five times the rate of new students starting college. A 2018 report from the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association found a 47% increase between 2013 and 2016 in depression diagnoses among 18-to-34 year-olds; the report attributed the rise largely to the fact that far more young adults are seeking help.

“Many of my clients joke that they and their co-workers often start conversations with, ‘My therapist thinks…’” says Elizabeth Cohen, a clinical psychologist in Manhattan, “The shame of needing help has been transformed to a pride in getting outside advice.”

One reason for the shift is celebrities such as Demi Lovato, Lady Gaga and Dwayne (“the Rock”) Johnson, who have publicly discussed their struggles with depression. Many therapists also credit social media—often criticized as a source of millennial distress—with helping to normalize mental illness and to remove any lingering stigma from seeking support. Vix Meldrew, 32, a London blogger, says that whenever she talks about mental health online, her response from readers skyrockets because she is “making them feel less alone.”

‘I think the therapist’s natural instinct to listen and not give advice can be challenging and threatening to millennials.’

Many younger people pursue therapy as another form of self-improvement and personal growth, not unlike yoga, meditation or “preventive Botox.” (A 2015 survey by the research firm Field Agent found that millennials spend $300 a month on such pursuits.) Some millennials also use life coaches. That includes Ali Wunderman, a 29-year-old freelance journalist in Whitefish, Mont. “My life coaching and my therapy work really well together,” she says. “It’s about forming habits and behaviors that lead to a fuller life.”

But young people are struggling to find such balance. A 2018 study of 40,000 American, Canadian and British college students published in the journal Psychological Bulletin found that millennials are suffering from “multidimensional perfectionism” in many areas of their lives, setting unrealistically high expectations and feeling hurt when they fall short. This propensity can motivate them to seek assistance when something goes wrong—but it also sometimes drives them to turn that assistance into dependence.

Some young people think “that the therapist is going to provide an answer rather than help them discover the answer within themselves,” says Dr. Cohen, the Manhattan psychologist. Dr. Cohen recalls one recent 20-something client who was unsure about whether to stay in a relationship. “It really felt like she had gone from therapist to therapist looking for one that would tell her what to do,” says Dr. Cohen. “I think the therapist’s natural instinct to listen and not give advice can be challenging and threatening to millennials.”

Technology has contributed to the expectation of a quick fix. Apps and online services such as Talkspace and MyTherapist offer therapy by phone, chat, video and message board, making it more likely that young people will opt for superficial bromides over meaningful long-term help. Used correctly, however, tech-based therapies can fill in important gaps, especially for millennials more comfortable facing their devices than a therapist. Julia Koerwer, 28, a graduate student in social work in Queens, N.Y., uses textlines when she needs immediate help. “People tend to think crisis hotlines are for suicide only,” she says. “But just to be like, ‘OK, it’s Wednesday, I see my therapist on Sunday, and I feel like [expletive] right now. What can I do?’ That’s helpful.”

New studies also show that young couples are using therapy before moving in together or in the early years of marriage—something virtually unheard-of in earlier generations. Kristina and her partner started couples counseling in 2017 when they got their first apartment together. “If my mom and stepdad weren’t communicating well, they’d be like, ‘Oh, let’s just talk about it over dinner,’” she says. “But we work late, and then at home we’re answering emails on our phones, and talking it out over dinner just doesn’t work that way anymore.”

For many, such “self-care” doesn’t feel like a chore. “I just enjoy therapy,” says Ms. Koerwer. “I don’t enjoy getting blood drawn—I’d be looking for ways to stop having to do something like that. But I like my therapist, I have a good relationship with him. It’s not like I’m trying to figure out, at what point can I stop doing this?”